”Within minutes of being on foil, the rest of the world fades away. We are skating downhill on uncountable numbers, shapes, and sizes of bumps.”

"This is stupid, I'm being such an idiot." "It's so simple!" "One time right!" "Countdown from 30 seconds; you're allowed to try again in 30 seconds." "I'm not paddling in." "I need to do this one time, and I'll be home in 10 minutes."

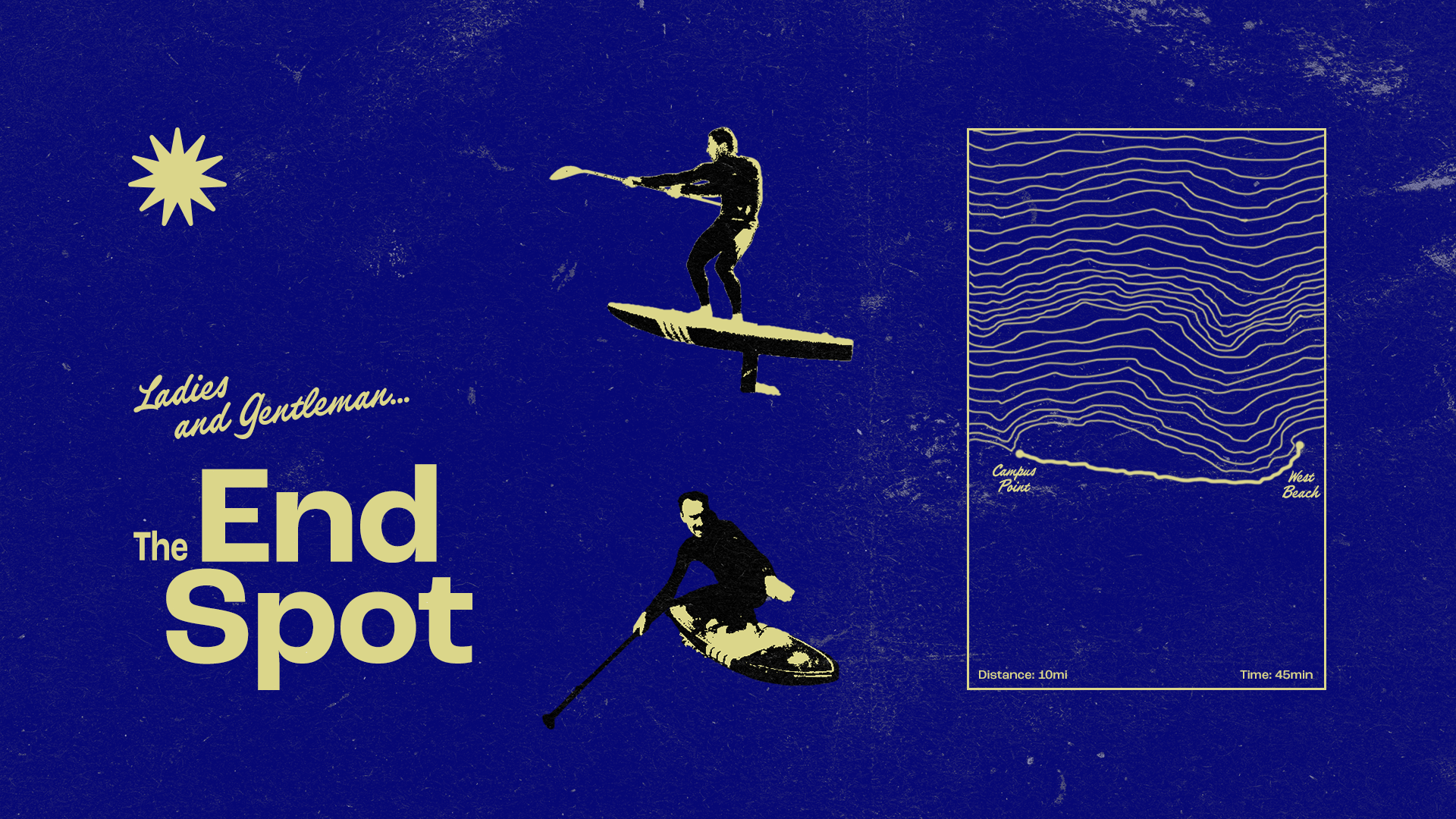

‘The End Spot,’ that's what my roommate, Davis, and I call our new apartment. Our place conveniently sits just one block away from Santa Barbara Harbor. And, the UCSB campus, and more importantly, Campus Point, is a perfect ten weaving coastline miles up the coast. Campus Point sticks out from the mainland, hence it being a point. It taps in closer to the channel winds than most of the local points, making it just the right combination of geography, wind, and waves for Downwinding. To start, we paddle our SUP foil boards out at Campus Point, making our way a hundred yards past the kelp line and into the wind line. Once we’re out and pop up on foil and look around, we are immediately, and somewhat unbelievably, a mile or more offshore as the coastline bends in and away from the point.

The bumps, what we all used to call waves before foiling happened, are organized, playful, and steep. Within minutes of being on foil, the rest of the world fades away. We are skating downhill on uncountable numbers, shapes, and sizes of bumps. We’re kind of flying in formation, speeding up and slowing down to ride together, holding our GoPro session with our bare hands, trying to get more creative with each wave ridden. Davis has mastered the "sit down" and the "boog foil," while I've perfected the "go straight as fast as I can while yelling" move; to each their own. I try a few sit-downs and end up crashing. The more we mess around, the more we fall, requiring the always sketchy process of popping back up again. The entire experience isn’t about speed, elegance, or distance, it’s just about enjoying each bump, each wave, finding the steepest ones, and seeing what might be done that hasn’t yet been explored.

Side note: Learning to get up on foil on a SUP foil has been one of the hardest things I've learned in recent years. I will put it like this: It's extremely hard. Sometimes, it feels impossible. To balance on the board in big wind and waves is challenging enough. Add to that, you have to paddle straight, generating enough speed and power to drop into a moving chop and gain a touch more speed for the foil to work. The act of multi-tasking to achieve the end effect is very rewarding, but the cost is also high. I have raced foiling catamarans and kite foils, and surf-foiled big bombies in the Mentawais, but somehow, paddling on this 75-liter board has been the most humbling. There is a fine line between flying down big ocean swells at 20 knots and sitting on a useless 6 foot carbon board with no means to ride to shore. It’s a classic Japanese proverb “Nana korobi ya oki,” which means 'Fall down seven times, get up eight.' But, once your muscle memory kicks in, you take your time, persevere, it clicks and becomes easy, like all things, with enough practice.

Side note #2: This "campus run" isn't the most friendly. Plenty of SB locals avoid this run for a few reasons. In SB, the wind loves to go offshore when it hits around 18 knots or a clearing breeze is happening. This is all geographical, and we call it "getting fluky." The campus run also sends you far offshore whether you want to or not, it’s again geographical. Once you cope with those things then there’s the risk of not completing the run and becoming stranded somewhere along the journey. There are only a few good spots to land on shore, and the likelihood you fall in just the right spot to hit one of those is low. Most of the coastline is bordered by Hope Ranch, which is great for views if you live there because it consists of big cliffs, but coming from oceanside, there isn’t a nice guided path to end your ride.

These types of sports come with an inevitable reality being confronted with swimming/paddling in from distances beyond desirable. The Coast Guard has been called on many a downwind foiler/kiter/winger, etc.. I’ve been forced to paddle in on a tiny kite foil plenty of times, which is a lot more like swimming with a weight than paddling. LUCKILY, I have yet to be that humbled SUP foiling. So far so good, I’ve made every "campus run" attempted without much drama.

Back to Davis and I having a blast. At this point, I’ve crashed and repeatedly popped back up about six times, but on the sixth time, the difficulty factor started to climb. The paddle wasn't gripping the same, I wasn’t able to generate much speed, so the effort was getting more intense with less result. I finally did pop up, but gigantically out of breath. I hit a wall. Which prompted my inner, wiser self to say, "Let's chill for a bit.”

As I sat and chilled I contemplated what was going on, haha, my excuses are as follows. One short week ago I was in bed for a week with some unknown, crazy infection. Once I was out of bed, I didn’t waste any time “recovering.” The first day back I went on a bike ride, the second, we did this same campus run. The next morning Davis and I did a sunrise run. Then by 11am the wind was on and we started the journey I’m relating above. Quite the training program, lie in bed for a week, get out of bed, grind for a few days, and then just expect everything to work like normal. Sitting there on my board contemplating my fate, I was more than a little tired.

15 minutes later, back up and foiling, but got a little lazy and let my wingtip pop out, and immediately it cavitated and I fell. Ignoring my lesson learned, I tried to pop up again. Tried another time. I was close. Options were running out. I'd either get up on foil and not be able to keep it going, or get up on foil and bobble and fall. I tried about five times. Sitting on my board again, my wiser inner self counseled once again. Now we need to take our time, let's do this "one time, right." I know I can't half-ass this. I counted down from 30 seconds and tried again, and again, and again. Roughly 15 tries later the possibility was mounting that maybe I wouldn't get back up. I paddled for 10 seconds on my stomach towards Leadbetter, the point just above SB Harbor that looked a little too far away than I'd hoped. After 10 seconds, I thought, "This is stupid," and tried to pop up again. I was so close! That was the frustrating part. I was so close to being a 10-minute foil from The End Spot.

My mindset means nothing. The distance to land doesn't change based on my thoughts. My experience means nothing; my confidence means nothing, my thoughts of sharks mean nothing. After what felt like hours, but was more like 30 minutes, I was humbled enough into maturity to accept my fate of the long paddle home.

The paddle in was a drag, but I made it. Hence the story. Ultimately, nothing truly dramatic transpired. My daily schedule was affected by maybe an hour or so. I was never really in any danger. I could have swum that distance if I had to, but when something doesn't go as planned, your mind can drift to darker places that don't feel comfortable. Bad decisions become much more possible, driven by the imagination run amok. Reason can be replaced by emotion, and a chill and fun situation can turn against you. The fear is good though. Respecting the ocean and understanding how prepared you need to be is good for you. But, being in the moment requires a steady hand.

If this were easy, and it came without risk, that nervous feeling on the walk out to the beach wouldn’t be there, there wouldn't be a sense of accomplishment actually completing a run successfully, that feeling of stoke and relief when you pop up on foil wouldn’t matter, and there wouldn’t be any adrenaline driven by not quite knowing exactly what will happen next. Being miles out in the open ocean, very much on my own, foiling on a small board, has opened up for me some of the rawest feelings I've ever had. That's why we do it.

We will be out there next time the wind is up, so join us.

Story by Quinn Wilson

Graphic by Davis Ulrich